Ecoengineering the Sacred

A speculation on the role of fungi in religious spaces

I’m usually careful when it comes to speculating about any seminal role fungi might have in culture. Writers have tied themselves in knots trying to prove psychedelic mushrooms were a catalyst for various religions, even tanking their careers, as happened to the dead sea scrolls scholar John Allegro when he suggested Christianity is derived from an Amanita muscaria cult in his book The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross.

Indeed, a few years ago I did a talk at the Athenaeum, a psychedelic library in midtown Manhattan that used to be next door to Sparks (famous for its stuffed clams and as the killing ground of mobster Paul Gambino in 1985), and a fellow asked if I was familiar with the story that Santa Claus was derived from Amanita muscaria-consuming shamans. The notion was first raised by the poet Robert Graves in his book Difficult Questions, Easy Answers (Cassell, London, 1972); elaborated by R. Gordon Wasson and others; and published by James Arthur in his book Mushrooms and Mankind. (Arthur ended up committing suicide while in a holding cell for suspected pedophilia in 2005). The idea has been repeated on a zillion websites, podcasts, and lectures since then, which is why, when I answered the questioner at the Athenaeum by saying the Santa hypothesis was cool speculation not fact, he looked like a kid who had just learned Santa didn’t exist at all and I could feel the vibe in the room shift away from me.

And now I am proposing something likewise dependent on correlation and speculation, and a certain suspension of disbelief. But life is short, and I think I’ve earned some fun. So here goes.

According to numerous architectural historians, the sacred grove, those clusters of trees that people all over the world believe house deities and spirits, is the model for sacred architecture from the Neolithic to the Gothic periods. I propose that the designation of some sacred groves occurred when human beings sensed--though did not see--the rich community created by the trees and their mycorrhizal fungi, what William James, in his Varieties of Religious Experience (Longmans, Green, and Co. NY 1902) described as “a feeling of objective presence, a perception of what we may call ‘something there,’ more deep and more general than any of the special and particular ‘senses.”

When people experience that sense of life they cannot see, it leads some to claim they are feeling the presence of deities or spirits. But maybe what they are experiencing is the sense of space created by the trees and their fungal symbionts.

Mycorrhizal fungi do not create groves, but they do define spaces by linking trees in an ecosystem and in some cases, inhibit the growth of underbrush. Fungi may play a role in tree selection by favoring those trees that share the most photosynthates. And these relationships may be ancient. In an old growth grove, there may be old growth fungi living as well.

I investigated the notion that maybe we can sense fungal life on a subconscious level, beyond moldy smells and immune reactions to floating spores. Fungi do produce pheromones for mating purposes, and some “fungal pheromone-sensing machinery” may also help the fungus locate plant hosts. More specifically, the fungus’ pheromone receptors may sense chemicals produced by a potential tree host. It’s a process called chemotropisim. But it is unknown if humans can sense fungal pheromones, either consciously or subconsciously. Maybe we don’t, maybe we do.

Fungally-derived spaces that we can see, however, have most certainly captured the human imagination. Fairy rings have been described in Northern European folklore as places where fairies and elves dance (but should a human stumble into the ring they too will be forced to dance until they go insane or pass out.) The Germans called them witches rings, the Dutch described them as where the devil churned his milk. But despite these variations on the story, fairy rings have traditionally creeped people out because they seem to be portals to other realms, realms that appear, magically, after it rains.

But here are how fairy rings are formed. Fungi live in their food and unobstructed, the fungus will grow in every direction it has food to grow into. So, in a meadow, let’s say the fungus is consuming dead grass roots. It grows in a circular fashion, consuming those grass roots. As the mycelium depletes its food source, the older cells of the fungus in the middle of the mycelium die off. What continues to live is an expanding ring of mycelium, its growing edge. A fairy ring occurs when the growing edge of the mycelium fruits. It’s like the fungus is alive where it is headed and dead where it was.

Fungi are microbes; mushrooms are visible. When we see a fairy ring, we are experiencing a product of microbial life. And the same may be true when we enter a grove. In the past, before the era of microscopes, no one even knew such a thing as microbes occurred. And that’s why, I think, the phenomena of fairy rings and groves have been historically attributed to supernatural forces. What we can’t see, or otherwise describe with our senses, gets bumped to a spiritual explanation.

Which suggests that in the case of groves and fairy rings anyway, yesterday’s fairies and witches and deities, may be today’s fungi.

So, let’s say that fungi participate in the creation of a grove. Some groves have been designated by people as sacred.

About Sacred Groves

Groves have a long history of worship in many ancient cultures (and some contemporary ones): the British, the Latins and Greeks, the Hindi, the pre-Buddhist Ban sect of Tibet, the Shinto of Japan, people from Russia, Indonesia and the African continent all worshipped among the trees.

As the Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca wrote in the 1st century, “if you come upon a grove of old trees that have lifted up their crowns above the common height and shut out the light of the sky by the darkness of their interlacing boughs, you feel that there is a spirit in the place, so lofty is the wood, so lone the spot, so wondrous the thick unbroken shade.” In certain groves of trees one can sense their difference from the surrounding woods. In very ancient groves, sometimes there are no surrounding woods anymore. The grove of Cupressus gigantean in the Giant Cypress Nature Reserve of Bajie, Tibet attracts pilgrims from all over China and the Himalayas. Much of Tibet is deforested, but this grove is holy in the native Ban faith, the religion that merged with Indian Buddhism to become Tibetan Buddhism. The grove is trashed with strings of faded, tattered prayer flags and the earth at the base of the trees is bare from countless tourists who wind among the stately trees with selfie sticks. But the grandeur of the grove? Unaffected. It simply dwarfs the idling busses and clicking cameras.

Photo: Eugenia Bone

The 3000-year-old Life Tree, as the Tibetans call it, is surrounded by about 25 ancient cypresses. Thick-bodied and twisted, with whiskers of shaggy red bark, these trees are so huge and solemn, so ancient it’s as if they’ve gained sentience. Walking amidst the trees, which I visited in 2011 with the mycologist Daniel Winkler, was like entering an amphitheater where a few giant people sat at random, conversing mentally. To be among those trees was otherworldly, like encountering gods.

All over the world groves have been held sacred by local people; most often groves consisting of a particular species of tree, but in many cases all the vegetation in a designated grove is venerated. “The protection of sacred groves is part of ancient human culture around the world and in every continent,” writes Nancy Cheng, an Associate Professor of architecture at the University of Oregon in her paper Sacred Groves and Temples: Resource, Religion, and Resistance. https://blogs.uoregon.edu/biosynergies/2011/06/09/sacred-groves-and-temples-resource-religion-and-resistance/ In the Mediterranean, the Greek and Roman landscapes were dotted with hundreds of sacred groves, like the famous sacred grove at Dodona, a group of oaks along the Titaness River in Epirus, Greece. The trees were thought to speak and issue prophesy. In Greek myth Jason and the Argonauts, the masthead of their ship, the Argo, gave them guidance. She was carved from one of the sacred trees. (One of my favorite movies, 1963’s Jason and the Argonauts, has a wonderful mysterious moment when the masthead speaks.)

Every community in the Caucasus Mountains in Russia had its own sacred grove. These were sanctuaries built among ancient trees which were never to be cut. The Baltic states held onto their sacred groves longer than others in Europe, like Tammealuse, a sacred grove in Estonia, where research done by the University of Life Science found that 65% of the people living in the southern part of the country today believe trees have souls. In Africa, it is taboo to cut down trees in mugumo groves. Composed of strangler figs (Ficus natalensis), it is held sacred by the Kikuyu people of Kenya. No branches may be broken, no firewood gathered, no grass burnt, nor wild animals killed. Nonetheless, many groves have been felled. Twentieth century missionaries and their local converts eradicated the Kikuyu’s traditional temples of worship, siting churches and schools where the groves once lived, co-opting the trees’ mysteries, and merging them with Christian mythology. In Indonesia, the Banyan tree (Ficus benghalensis Linn) is considered sacred. Local people believe that spirits reside within them and ensure the availability of clean water. Indeed, what is believed to be the activity of spirits could be the Banyan tree’s own anti-bacterial properties present in the aerial roots, bark and leaves which can influence the quality of nearby water sources for human consumption. I have long held that if you look under the hood of many stories that attribute supernatural machinations to natural phenomenon, you will find microbes. It’s like my son Mo once said to me: It makes less sense that God is one big entity, but rather, billions and billions of tiny ones.

Throughout history, combatants have tried to crush their enemies’ resolve by destroying the religious symbols that unify them. A great Druidic grove near Marseilles in southern Gaul was cleared by Caesar’s troops to remove the spiritual powers the Gauls believed were inherent in it. This practice was repeated over and over during the Roman wars with Celtic peoples. For example, the groves on the island of Anglesey, a British druidic stronghold, were destroyed by the Roman general Gaius Suetonius Paulinus as part of a pogrom to eviscerate the spiritual heart of the rebellious Britons. During the ten years of the Cultural Revolution (1966 to 1976), Maoist troops seeking to dominate China destroyed many sacred forests, like the “holy hills” of the Dai people of Yunnan Province.

UNESCO includes several living groves recognized for their spiritual value, like the Central Eastern Rainforest Reserves in Queensland, Australia, sacred to the Aborigines; a sacred grove of betel trees is still used by priests in rice ceremonies in the mountain rice terraces of Luzon, the Philippines; and the Forest of the Cedars of God in Lebanon, trees imbued with such spiritual import that crusading knights brought seedlings back to Europe where they were planted in churchyards, monasteries, and around the chateaus of nobles.

An allée of cedars of Lebanon, in La Romieu, France Photo: Eugenia Bone

From Sacred Groves to Woodhenges

Sacred Groves are thought by many scholars to be the first temples. The 18th century antiquarian William Stuckeley argued that all temples of the Neolithic, or stone age were modeled on sacred groves. Even the construction of Solomon’s Temple might be based on a sacred grove. The original layout was built in 960 BC in Jerusalem and was supposedly based on the Garden of Eden, arguably one of Western literature’s seminal sacred groves. Here’s a cool YouTube on the temple.

Neolithic people were the first farmers and, subsequently, the first great deforesters. Their monumental structures may mark the point of transition when humans first settled into agricultural societies. Forests were disappearing under the plow, but sacred groves, which had a history of veneration by earlier hunter gatherers, were protected, according to the Nancy Cheng, from agricultural clearing. Groves became isolated patches of the original forest that were integrated into agricultural culture, and the deities that occupied these spaces evolved into deities that could ensure a good harvest or, if angered, bring famine.

Some of civilization’s most ancient temple and monumental architecture seem to be stylized versions of sacred groves. The earliest temples built during the Neolithic era were artificial wooden groves made of felled, transported, and re-erected tree trunks. In fact, the first stage of Stonehenge in southern England, among the world’s most famous prehistoric monuments, was a circular foundation ditch in which rings of timbers were erected. Nearby are the remains of Woodhenge, built about 2500 BC, a monument originally composed of six concentric rings of timber posts aligned with the summer solstice. The remains of another timber monument in the immediate area are aligned to the winter equinox. The posts are long gone, of course, but archaeologists can tell where they once were. As wood decays, particles of soil slip in and fill the gaps. Eventually the entire hole is filled with soil that’s of a slightly different color and texture than the undisturbed soil around it. From the depth and size of the post hole, archeologists can estimate how large the original timber was, and how much was standing up out of the ground. The cut timbers of Woodhenge were up to six meters high and crowded together. It would have been a formidable place of towering tree trunks and shadows. At the center of Woodhenge archeologists found the 2100-year-old grave of a sacrificed child, its scull split with an ax. Another “woodhenge” of the same age lies near Pommelte, Germany. It is composed of multiple rings of wooden posts, a palisade, a bank, and a ring of ditches containing the remains of bound adolescents. Sacrifices, whether they are flowers or bread or children, are offerings to a deity or deities. This suggests that woodhenges, also known as timber circles, while having astronomical purposes, were also homes of gods or spirits.

There are woodhenges in the USA as well. Just northeast of Cincinnati are the remains of the 2000-year-old timber Moorehead Circle, once a leafless forest of wooden posts built by the Ohio Hopewell culture during the Woodland Period (11,000 CE), and part of a massive collection of earthworks just northeast of Cincinnati. In 2021, archaeologists began using computer models to analyze the Moorehead Circle’s layout and found that Ohio’s woodhenge is an intentional astronomical alignment. Three hundred fifty miles west lies the Cahokia woodhenge across the Mississippi river from St. Louis.

I went to St. Louis in March hoping to gain some insight into the religious practices of the archaic Mississippian culture, something I could apply to this crazy idea about fungi and sacred architecture. I came back with the emails of three Missourian witches.

Let me explain.

The Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site in Illinois, just west of St. Louis is the largest and considered the most sophisticated prehistoric site north of the Rio Grande. It once covered 4,000 acres and included at least 120 mounds, including the Monk’s Mound, a rectangular earthwork that rises ten massive stories into the air. Cahokia was larger than London at its apex--around AD 1120--with some 15,000 souls living in single family dwellings surrounding the ceremonial structures. The Cahokia Mounds Museum Society raises money for the site and operates events like a 5K trail run and equinox visits to the reconstructed woodhenge.

That’s what I went to see: the spring equinox. It was chilly and damp and maybe fifty of us stood about in the murky blue predawn light, steaming thermoses in hand, scarves around our throats, hearts in our throats, standing still as the earth beneath us tilted toward spring. Bill Iseminger, an anthropologist who has devoted his career to Cahokia, clambered up a ladder to explain what we were about to witness, the muffled roar of Interstate 70 in the background, like the sound of wind.

Built by the Mississippian culture 2100 to 3000 years ago, this woodhenge--like most others--is thought to be a solar calendar, marking the equinox and solstice for the timing of the agricultural cycle, even though there are more posts in the henge than needed for agricultural purposes. Indeed, the henge was enlarged over the years with additional posts, 12 posts at a time, until arriving at 72-posts which increased the diameter of the circle. Why this expansion happened is unknown. The posts are cedar, a sacred wood to some contemporary indigenous people. Cedar sustains indigenous life in diverse ways, and those ways may reach back a millennium: it is used for building, clothing, medicines (cedar has antimicrobial properties) and ceremony. The archaeologists at Cahokia Mounds think cedar may have been favored because it was the only native evergreen in the area at the time, symbolic of life and continuity, and because it has a red heartwood, symbolic of blood. I’d venture to add the local Eastern Red Cedar might have also had the stature necessary for the job. They can grow up to 65 feet tall and 25 feet wide. Anyway, the posts were cut and shaped with stone axes. The first reconstructed post was made with a stone ax. “You don’t realize how many limbs a cedar tree has until you try to cut them off with a stone ax,” commented Mr. Iseminger to the chilly crowd.

And then it happened. An orange glow emerged from the east, strongest between two timbers that framed the Monk’s mound, though the sun rose at the base of the mound, bigger and bigger and brighter and brighter until it hurt to look.

Photo: Eugenia Bone

Afterwards I managed to get myself invited to join Bill Iseminger and board member Ken Williams and their wives for biscuits and coffee at a nearby diner. I tried to maneuver the conversation toward the idea of the woodhenge being derived from sacred groves, but Bill pretty much put the kibosh on that. He explained that Cahokia was in a flood plain with few large tree species, though on the bluffs to the west there were forests where the original woodhenge timbers probably came from. I tried another tack. Maybe the presence of mycorrhizal fungi participated in the designation of a sacred grove, and therefore all subsequent sacred architecture like the woodhenge had fungal origins, and they looked at me in a way particular to Missourians. Yeah, said Bill’s lifted eyebrows and the tilt of his head, sure. Show me.

Once the sun was high and hot in the sky, and the magic hour long past, I pulled into the little parking lot next to the Monk’s Mound to make a few notes, the earthwork heaving in my rear-view window. Within a few minutes a car pulled up and parked beside me and out jumped three women in capes. I watched them pull themselves together, their keys and purses and fluttering garments, watched them lock their car and head up toward the 154 steps of the mound.

Of course, I followed them.

Photo: Eugenia Bone

About halfway up the mound I finagled an opportunity to ask,

“What’s with the capes?”

They were shy at first, I guess fearful I’d get all Christian on them, but they eventually revealed they were pagans and there to celebrate the equinox. I asked if I could watch their ritual and they said Okay.

We walked to the top of the mound and found a grassy spot out of the range of the running dogs and toddling children, and the ladies, all middle-aged and smiling, a blond, a redhead, and a grey-haired woman, sat at three points of the compass. Since their fourth companion was a no-show, they let me stand in for the west. With the sun in my face, we felt the mound underneath us and thought about what we hoped for, and we hoped for what we thought was important and good, and the blond pushed her cape aside to reveal she was dressed in the colors of Ukraine. We waited, our bodies humming in the sun, until 10:33AM Central, the exact moment spring began in that place in 2022. Then we hugged and shared a bit of lemon cake, which was already portioned into four pieces so there was one for me, and we talked about our kids a little, but it got hot, so we gathered ourselves together and walked back to the cars.

When the witches realized that I had been parked next to them all along, their eyes widened.

“Oh my god!” exclaimed the redhead. “What are the chances?”

From Henges to Temples and Cathedrals

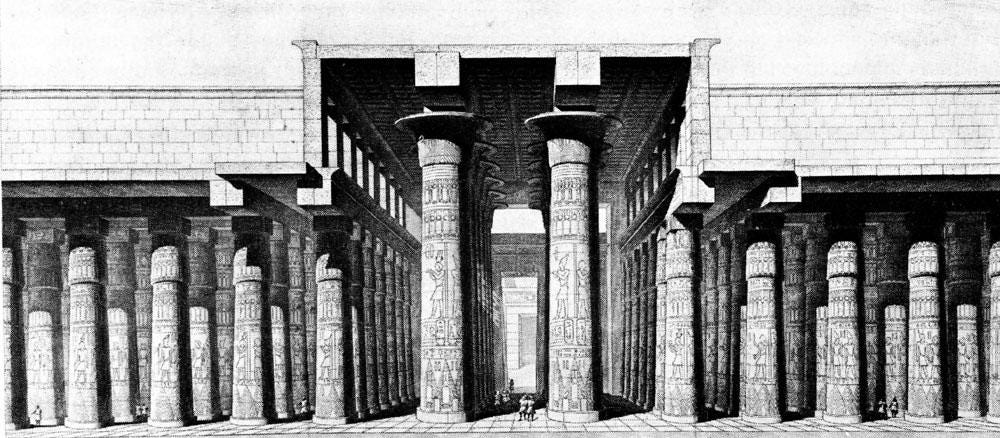

Cohokia, Woodhenge, and Stonehenge are what the late architectural historian Vincent Scully describes in his book, The Earth, The Temple, and the Gods (1962) as “man-made groves.” (The mysterious axe engravings on the megaliths at Stonehenge make sense in this context, though they are of Bronze Age.) Indeed, the sacred grove is a model that informs temple architecture from pharaonic Egypt to classical Greece to the pillared Gothic cathedrals of Europe. The 50,000 square foot hypostyle hall of Karnak is overwhelming, something like the redwood grove Avenue of the Giants, in Northern California: they are not on a human scale; more like the scale of a god. The 134 columns in the hypostyle—a colonnaded entrance to the inner sanctum--are up to seven stories tall and ten feet in diameter (about the size of a large Eastern Red Cedar). It would take six people touching finger to finger to hug its base. The columns are modeled after the shafts of papyrus, the native Nile delta plant that had many important uses in ancient Egyptian civilization.

Hypostyle Hall at Karnak, from a nineteenth century reconstruction

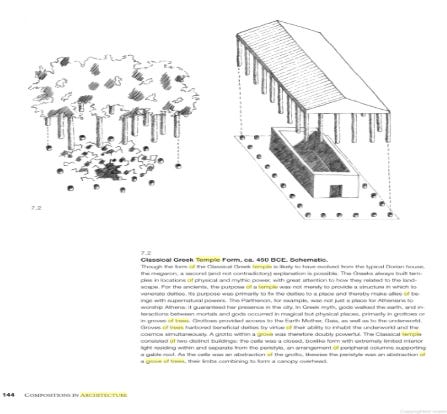

It is well established that a variety of column types are modeled on plant stems. The earliest Doric columns of Greek architecture were substitutes for wooden tree trunks that had once served the same purpose. Corinthian columns are “treelike,” according to Vincent Scully, and in the great Ionic temples, at Samos, Ephesus and Didyma, “the intention seems primarily to have been to form a grove.” In some classic Greek architecture, colonnades have no apparent structural import. Used only for temples, Scully suggested the colonnades were meant to articulate the shrine building inside. I propose that the colonnade is derived from a grove, with the sacred temple within representing a kind of holy focus that in groves might be embodied by a spring or dominant tree, but in temples, would usually contain a depiction of the god.

Diagram from Compositions in Architecture by Don Hanlon (Wiley, 2009)

If, as Scully suggests, some classic temple architecture is derived from sacred groves, then might we consider the vast columned spaces of Gothic cathedrals as deriving from them as well?

Note: I have a side interest in spaces that are composed of very old, large trees. The massive red wooden columns of the Hall of Eternal Peace at the Jongmyo Shrine in Seoul; the Temple of Heaven in Beijing; The Jokhang Temple in Lhasa. This is one of the oldest timber buildings in the world. The innermost part of the building was built in 647 AD of Tibetan juniper timbers (Juniperous tibetica) that were 500-plus years old when they were felled, and they still hold up the roof. Tibetan juniper is a high altitude confer, stubby and strong. The wood is used for building, as in the temple, the foliage for foraging goats, and the bark for piney aromatic incense that is likely antimicrobial. It is a common ingredient in Tibetan incense, thought to open nasal passages and the respiratory tract. Indeed, the inside of the temple reeked of Juniper incense, and was sticky with butter lamps. On my visit, we walked from one room to the next, among a roiling mass of colorfully clad worshippers who, when they jostled us, stuck out their tongues to prove they were not the devil—the devil’s tongue is forked--and so meant no mischief, performing their devotional circumnavigation as we shuffled along with them, catching the crinkly smiles of the women and men who patted us as we walked along, feet sticking to the tacky floor like walking on fresh paint. Jokhang is a working temple, not a museum. There are cases of bottled water piled on the floor, and monks in their red drapery clean the gilded buddhas and remove yak butter from overfull urns. It is woody and red and murky, like being inside a grove of trees. It’s the most sacrosanct of spaces, a great holy center like the Vatican, but deeply funky and common. Someone might have a revelation, someone might pee in the corner, and the entire place hums with murmured prayers like a great, buttery beehive.

Gothic church architecture, which first appeared in the early 12th century in Northern France, is inspired by trees, with columns for trunks, and pointed arches where the tree canopies meet. The German art historian Wilhelm Worringer, wrote in Form in Gothic (1911) the gothic style is “the expression in stone of the Celtic tradition, simulating… European primeval forests.” Nineteenth Century romantics embraced the Gothic style for its celebration of nature. “In Romantic ideology,” writes David Blayney Brown of the Tate in the UK, “nature was both the product of divine will and the source of Gothic form.” And while critics of different nationalities argued about whose country owned the style, “almost all agreed on its organic roots.” At the end of the day, as the poet Samuel Coleridge pointed out, the Gothic cathedrals of York, Milan or Strasbourg all looked like sacred groves that had been “awed into stone at the approach of the true divinity.”

Peter Young said it simply, in his book Oak (Reaktion Books, 2013). “I am certain all sacred buildings…derive from the natural aura of certain woodland or forest settings. In them we stand among older, larger, and infinitely other beings, remoter from us than the most bizarre other nonhuman forms of life: blind, immobile, speechless…waiting, altogether very like the only form a universal god could conceivably take.”

So, in conclusion: a development path of spiritual architecture may well have started with sacred groves, then evolved into woodhenges and stonehenges, which led to classical temples and gothic churches. If you buy the premise that a grove may be designated as holy in part due to its ecology—a collaboration of trees and fungi—then one can imagine the architectural lineage I’ve described might be derived from that seminal relationship.

Which would suggest that the original engineer of sacred space is fungal.

What I appreciate about this piece is the quality of research. Turns of phrase and visual imagery abound in the writing, but it’s the author’s plethora of well-documented examples from around the globe - often collected by her firsthand - that I found most compelling. Thank you.

What a great essay, thank you Ms. Bone! I never heard of "woodhenges" before.

I read somewhere long ago that sacred church architecture was modeled after vaginas. Or vulvas. I'm never clear on which word includes which parts of the apparatus down there. But basically the top of arches and the arched ceilings of cathedrals being similar to the apex of the inner labia topped by the tiny but grand clitoris. I thought this made sense also in terms of "portals." The vagina as a doorway to life, the cathedral a doorway to God.

After reading your essay, it makes a lot more sense that steeples and cathedral ceilings were modeled after sacred groves. It's probable not all early architects were so obsessed with body parts.

The fungal aspect is intriguing. i know from foraging that mushrooms are more plentiful in older forests. Wherever the underground mycelium has lived longest undisturbed by tree felling, the greater the abundance of fungi, in my experience. There is the "presence" you speak of, that I know we have all felt somewhere in the woods, standing before a great mother tree, for example. You attribute that otherworldly sensing to potentially an underground mycelial network. Maybe. But fungi are everywhere, in the cells of leaves, in lichen, in dead and living wood, yeasts and molds floating around in the air. Maybe it's soil fungi in particular that give a place its soul.

Thanks again for your work!